Escherichia coli (abbreviated as E. coli) is a commensal (normal flora) in the gut of humans and warm-blooded animals. Most strains of E.coli are harmless, some even benefit the hosts by producing vitamin K in the gut. Some strains, however, can cause severe foodborne diseases.

Some strains of E. coli have evolved into pathogenic E. coli by acquiring virulence factors through plasmids, transposons, bacteriophages, and/or pathogenicity islands. Pathogenic intestinal E. coli may be classified into four strains based on the diarrhea-causing mechanism. They are; enterohemorrhagic (EHEC), or verotoxigenic (VTEC), enterotoxigenic (ETEC), enteropathogenic (EPEC), and enteroinvasive (EIEC), or enteroaggregative (EAEC).

You may like to read: Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli

Exotoxins-producing strains of Escherichia coli can cause watery (non-bloody) diarrhea and bloody diarrhea depending on the exotoxin they produce. For example, enterotoxigenic strains of Escherichia coli are a common cause of watery diarrhea (also known as traveler’s diarrhea) in developing countries.

Table of Contents

Diseases caused by E. coli

- Urinary tract infections (UTI): E.coli is the most common cause of both community and nosocomial urinary tract infections; E.coli causes more than 75% of cases of UTI.

- E.coli is the second most important cause of Gram-negative rod sepsis

- Perinatal infection with E.coli (exposure of newborn to E.coli colonized in the birth canal of the mother during natural birth) is the predominant cause of neonatal meningitis

- Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is responsible for the traveler’s diarrhea (watery diarrhea)

- Enterohemorrhagic strains of E.coli (i.e., shiga toxin-STx producing E. coli ) cause bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS).

Characteristics of E. coli

- Gram stain: Escherichia coli is a straight gram-negative short rod or bacilli

- Escherichia coli cells are small rods 1.0-2.0 micrometers long, with a radius of about 0.5 micrometers. However, the size varies with the medium, and faster-growing cells are larger.

- E. coli is the most abundant facultative anaerobe in the colon and feces.

- The generation (doubling) time of Escherichia coli is 20 minutes.

- E.coli are lactose fermenters that give pink colonies in MacConkey agar (this property distinguishes E.coli from Salmonella and Shigella-two most common intestinal pathogens)

- Antigenic properties: There are more than 1000 antigenic types of Escherichia coli.

a. O-cell wall antigens (>150 types)

b. H- flagellar antigen (>50 types)

c. K- capsular antigen (>90 types)

Virulence Factors of E.coli

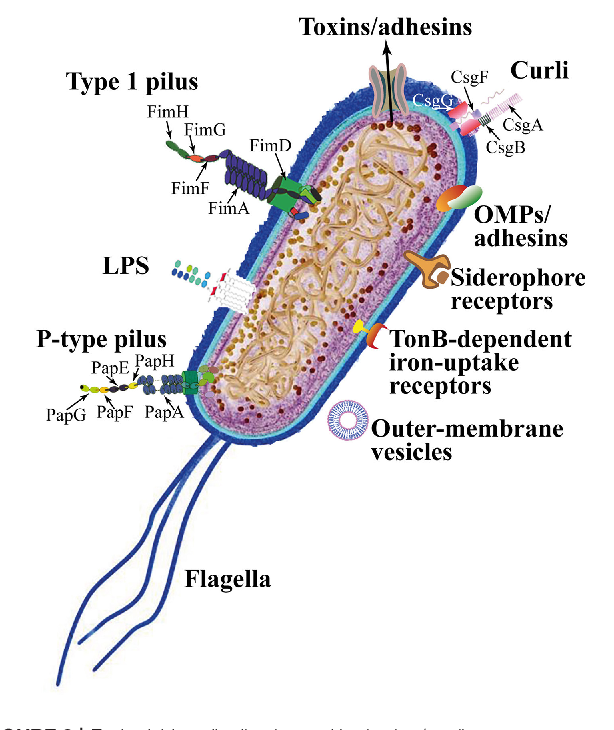

- Pili: Helps in adherence of organisms to the cells of jejunum and ileum in case of intestinal tract infection; urinary tract epithelium in case of urinary tract infections.

- Capsule: Interferes with phagocytosis, and plays the main role in systemic infections.

- Endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide): Responsible for several features of gram-negative sepsis such as fever, hypotension, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- Exotoxins e.g. enterotoxin act on the cells of the jejunum and ileum to cause diarrhea. Other exotoxins are verotoxin, Shiga-like toxin, etc.

Diagnostic Features of E.coli

Scheme for Rapid Identification of E. coli.

- Colony Morphology: E.coli ferments lactose and produces pink colonies on MacConkey Agar. Typical colonies of Escherichia coli on MacConkey agar will appear pink and shiny and have a diameter of 0.5 to 1 mm after overnight incubation. Colony appearance varies from grey to white, transparent to opaque, and raised convex to flat on blood agar plates. However, some E.coli belonging to the Alkaligens-Dispar (A-D) group may be non-lactose fermenting on Mac-Conkey agar. (E.coli O157: H7 does not ferment sorbitol, which serves as an important criterion that distinguishes it from other strains of E. coli)

- On EMB agar, E. coli produces a characteristic green sheen.

Biochemical Tests

- Indole positive: produces indole from tryptophan

- It is motile

- It decarboxylates lysine

- It uses acetate as the only source of carbon

Other important biochemical tests of E. coli are summarized in the table below.

| Characteristics | E.coli |

| Catalase test | Positive |

| Oxidase test | Negative |

| Nitrate reduction test | Positive |

| Methyl-Red (MR) test | Positive |

| Voges-Proskauer (VP) test | Negative |

| Citrate utilization test | Negative |

| Acetate utilization test | Positive |

| Indole test | Positive |

| Pyrrolidonyl-β-naphthylamide (PYR) test | Negative |

| H2S production test | No |

| Urease test | Negative |

| Oxidative-fermentative (OF) test | Fermentative |

| MUG test | Positive |

| TSI reactions | Acid/Acid, Gas, |

| SIM | No H2S, Indole +ve, motile |

| Motility | Motile |

| Phenyl Pyruvic acid (PPA) test | Negative |

| Lysine decarboxylation test | + |

| Arginine decarboxylation test | -/+ (strain variability) |

| Ornithine decarboxylation test | +/- (strain variability) |

| ONPG | + |

| Sugar fermentation test | |

| Glucose | Yes |

| Sucrose | No |

| Lactose | Yes |

| Mannitol | Yes |

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Perform the susceptibility test by a disc-diffusion method using standard methods described in the guidelines. To detect ESBL-producing E.coli, the isolate screened should be multidrug-resistant exhibiting resistance to at least one of the third-generation cephalosporins.

Extended-spectrum ß-lactamases (ESBL) are a rapidly evolving group of ß-lactamases that can hydrolyze third-generation cephalosporins and aztreonam but are inhibited by clavulanic acid. Increasing resistance to third-generation cephalosporins amongst E. coli is predominantly due to the production of ESBLs. These plasmid-mediated enzymes mostly evolved via point mutations of the classical TEM-1 and SHV-1 β-lactamase.

Screening test for ESBL producing E.coli

According to the CLSI guidelines, isolates showing an inhibition zone size of ≤ 22 mm with ceftazidime (30 µg), ≤ 25 mm with ceftriaxone (30 µg), and ≤ 27 mm with cefotaxime (30 µg) are identified as potential ESBL producers and shortlisted for confirmation of ESBL production.

Confirmatory tests for ESBL

According to CLSI guidelines, two phenotypic methods can confirm ESBL producers:

Combination disc method

This test requires using a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic disc alone and in combination with clavulanic acid. In this study, a disk of either ceftazidime (30µg)/ cefotaxime(30µg) /cefpodoxime (30µg) alone and a disk of corresponding clavulanic acid either ceftazidime – clavulanic acid (30 µg/10 µg)/ cefotaxime – clavulanic acid (30/10 µg)/cefpodoxime – clavulanic acid (30/10 µg) is used. Both the disks are placed at least 25 mm apart, center to center, on a lawn culture of the test isolate on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plate and incubated overnight at 37°C. The difference in zone diameters with and without clavulanic acid is measured.

Interpretation: An increase of ≥ 5 mm in inhibition zone diameter around the combination disk of cephalosporin- clavulanic acid versus the inhibition zone diameter around the cephalosporin disk alone confirms ESBL production.

Double disc synergy method

This test requires two discs of a third-generation cephalosporin, either cefotaxime, ceftazidime, or cefpodoxime. A ceftazidime 30µg disc and an amoxicillin+ clavulanic acid 20+10 µg disc are placed 25 – 30 mm apart, center-to-center on a lawn culture of the test isolate on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plate. Incubate overnight in the air at 37°C.

Interpretation: ESBL production is inferred when the clavulanate expands the zone of inhibition around the ceftazidime disc in a cloverleaf fashion.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains cause 70 to 90% of community-acquired urinary tract infections (UTIs) in an estimated 150 million individuals annually and about 40% of all nosocomial UTIs. Various virulence genes are associated with Escherichia coli-mediated urinary tract infections.

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)

Uropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli express distinctive bacterial properties, products, or structures (virulence factors) that help them to overcome host defenses and colonize or invade the urinary tract.

Compared to commensal E. coli, uropathogenic E.coli are better adapted to the urethra and cause a greater proportion of UTIs. The more virulence factors a strain expresses, the more severe infection it can cause.

Virulence factors of recognized importance in the pathogenesis of urinary tract infection (UTI) are:

- Adhesins (P fimbriae, certain other mannose-resistant adhesins, and type 1 fimbriae): By attaching to host structures, it avoids being swept along by the normal flow urine and eliminated. Attachment is a necessary first step in colonization and a precedent for invasive infection in many situations.

- K antigen (capsular polysaccharide): They coat the cell, interfering with 0-antigen detection and protecting it from host defense mechanisms. The capsule has antiphagocytic and anticomplementary activities. The degree of impairment of phagocytosis is proportional to the amount of polysaccharides.

- Resistance to serum killing: Acidic capsular polysaccharides and the Kl capsule contribute to virulence by shielding bacteria from phagocytosis and possibly from serum killing, partly by blocking the activation of the alternative complement pathway.

- Hemolysin: Cytolytic protein toxin that lyses erythrocytes of all mammals

- Aerobactin system: E.Coli uses aerobactin to sequester Iron.

References and further readings

- Authors. Levinson W, & Chin-Hong P, & Joyce E.A., & Nussbaum J, & Schwartz B(Eds.), (2020). Review of Medical Microbiology & Immunology: A Guide to Clinical Infectious Diseases, 16e. McGraw Hill.

- Michael A Noble, Bailey and Scott’s Diagnostic Microbiology, Eleventh Edition. Betty Forbes, Daniel F. Sahm, and Alice S. Weissfeld. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 2002