Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) acid-fast staining technique is used to stain Mycobacterium species, including M. tuberculosis, *M. ulcerans, M. leprae,**and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM).*Detection of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) in stained and acid-washed smears examined microscopically may provide the initial bacteriologic evidence of the presence of mycobacteria in a clinical specimen. Smear microscopy is the quickest and easiest procedure that can be performed.

Mycobacteria’s cell wall contains high lipid concentrations, making them waxy, hydrophobic, and impermeable to routine stains such as the Gram Stain. They are also resistant to acid and alcohol and are described as acid-fast bacilli (AFB)or acid alcohol fast bacilli (AAFB).

There are two procedures commonly used for acid-fast staining:

- Carbolfuchsin methods which include the Ziehl-Neelsen and Kinyoun methods (light/bright field microscope)

- Fluorochrome procedure using auramine-O or auramine-rhodamine dyes(fluorescent microscope).

Principle of Ziehl-NeelsenMethod of Acid-Fast Staining

Mycobacteria, which do not stain well by Gram stain, stains well with carbol fuchsin combined with phenol.

- In the ‘hot’ ZN technique, the phenol-carbol fuchsin stain is heated to enable the dye to penetrate the waxy mycobacterial cell wall.

- In the ‘cold’ technique known as Kinyoun Method, stains are not heated but the penetration is achieved by increasing the concentration of basic fuchsin and phenol and incorporating a ‘wetting agent’ chemical.

The stain binds to the mycolic acid in the mycobacterial cell wall. After staining, an acid decolorizing solution is applied. This removes the red dye from the background cells, tissue fibres, and any organisms in the smear except mycobacteria which retain (hold fast to) the dye and are therefore referred to as acid-fast bacilli (AFB).

Following decolorization, the sputum smear is counterstained with malachite green, or methylene blue which stains the background material, providing a contrast color against which the red AFB can be seen.

Among the Mycobacterium species, M. tuberculosisand M. ulcerans are strongly acid-fast. When staining specimens for these species, a 3% v/v acid alcohol is used to decolorize the smear, whereas M. leprae is only weakly acid-fast. 0.5-1% v/v decolorizing solution is therefore used for M. leprae smears and also different staining and decolorizing time.

Note: 0.5% Acid alcohol or 5% Sulphuric acid is used for Atypical AFB because they (eg. Mycobacterium leprae, Nocardia asteroides) are much less acid and alcohol fast than Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli.

Sample Collection & Preparation

Due to overnight accumulation of secretions, first morning specimens are more likely to yield better recovery of AFB.

- Direct Smear: Smear prepared directly from a patient specimen prior to processing.

- Indirect Smear: Smear prepared from a processed specimen after centrifugation (is used to concentrate the material)

Reagents required

- Carbol fuchsin stain (filtered)

- Acid alcohol 3% v/v (or 20% sulfuric acid)

- Malachite green 5 g/l (0.5% w/v) or Methylene blue, 5g/l

Ziehl-Neelsen Staining Procedure

Procedural note

- Acid alcohol is flammable; therefore, use it with care.

- Take great care while heating carbol fuchsin (as the staining rack may contain volatile chemicals) to reduce the fire risk.

- Slides must not touch each other when placed on a staining rack to prevent the transfer of materialfrom one slide to another.

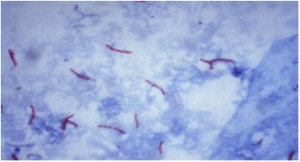

Results of Acid Fast Staining

- AFB: red, straight, or slightly curved rods, occurring singly or in small groups, may appear beaded.

- Cells: green

- Background material: green

| Reagent | Acid Fast | Non-Acid Fast |

|---|---|---|

| Carbol fuchsin with heat | Red (hot pink) | Red (hot pink) |

| Acid alcohol | Red | Colorless |

| Methylene blue/malachite green | Red | Blue/green |

Grading of sputum smear forMycobacterium tuberculosis

Sputum smear is graded as scanty, 1+, 2+, and 3+.

| Observation | Grading |

|---|---|

| No AFB seen while observing more than 300 fields | No AFB seen |

| 1-9 AFB/100 fields | Report the exact number |

| 10-99 AFB/ 100 fields | Report as 1+ |

| 1-10 AFB/field at least in 50 fields | Report as 2 + |

| More than 10 AFB/field at least in 20 fields | Report as 3+ |

- When no AFB is seen after examining 300 fields, report the smear as ‘No AFB seen’.

- When very few AFB are seen i.e. when only 1 or 2 AFB are seen after examining 100 fields, request a further specimen to examine (that AFB might have come from tap water (saprophytic mycobacteria), or it may be scratch of a glass slide or by the use of the same piece of blotting paper while drying.

- When any red bacilli are seen, report the smear as ‘AFB positive’ and give an indication of the number of bacteria present as follows (the greater the number, the more infectious the patient).

Advantages

- Microscopy of sputum smears is simple and inexpensive, quickly detecting infectious cases of pulmonary TB;

- Sputum specimens from patients with pulmonary TB – especially those with the cavitary disease – often contain sufficiently large numbers of acid-fast bacilli to be readily detected by microscopy.

Limitation of AFB Microscopy

- Does not distinguish between viable and dead organisms

Follow-up specimens from patients on treatment may be smear-positive yet culture negative

- Microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cannot distinguish drug-susceptible from drug-resistant strains.

- Limited sensitivity

High bacterial load 5,000-10,000 AFB /mL is required for detection ( In contrast, 10 to 100 bacilli are needed for a positive culture). Smear sensitivity is further reduced in patients with extra-pulmonary TB, HIV-co-infection, and those with disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM). Many TB patients have negative AFB smears with a subsequent positive culture. Negative smears do not exclude TB disease.

- Limited specificity

All mycobacteria are acid-fast Does not provide species identification Local prevalence of MTB andNTM determine the predictive values of a positive smear for MTB

List of Acid Fast Organisms

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Mycobacterium leprae(weak acid-fast)

- Other Mycobacteria

- Nocardia spp: Partial acid-fast

- Rhodococcus spp: Partial acid-fast

- Legionella micdadei: Partially acid-fast in tissue

- Cyst of Cryptosporidium: Acid-fast

- Cyst of Isospora: Acid-fast

Sodium Hypochlorite Centrifugation Technique to Concentrate AFB

This technique is used to concentrate the AFB present in sputum, as it increases the chances of detecting AFB in sputum smears. Sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) is recommended for liquefying the sputum, as it kills M. tuberculosis, making handling specimens safe for laboratory technicians.

Procedure

- Transfer 1-2 ml of the sputum’s purulent part (i.e. containing any caseous materials) to a screw cap universal bottle or other containers of 10-20 ml capacity.

- Add an equal volume of concentrated sodium hypochlorite (bleach) solution and mix well.

- Leave at room temperature for 10-15 minutes, shaking at intervals to break down the mucus in the sputum.

- Add about 8 ml of distilled water and mix well.

- Centrifuge at 3000 g for 15 minutes. When centrifugation is not possible, leave NaOCl-treated sputum to sediment overnight.

- Remove and discard supernatant fluid using a glass Pasteur or plastic bulb pipette. Mix the sediment.

- Transfer a drop of well-mixed sediment to a clean scratch-free glass slide and spread the sediment to make a thin preparation and allow air-drying.

- Heat fix the smear, stain it using the Ziehl-Neelsen technique, and examine it microscopically.

References

- Van Deun, A., Hossain, M. A., Gumusboga, M., & Rieder, H. L. (2008). Ziehl-Neelsen staining: theory and practice. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 12(1), 108–110.

- Chen, P., Shi, M., Feng, G. D., Liu, J. Y., Wang, B. J., Shi, X. D., Ma, L., Liu, X. D., Yang, Y. N., Dai, W., Liu, T. T., He, Y., Li, J. G., Hao, X. K., & Zhao, G. (2012). A highly efficient Ziehl-Neelsen stain: identifying de novo intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis and improving detection of extracellular M. tuberculosis in cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of clinical microbiology, 50(4), 1166–1170. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.05756-11

- Laifangbam, S., Singh, H. L., Singh, N. B., Devi, K. M., & Singh, N. T. (2009). A comparative study of fluorescent microscopy with Ziehl-Neelsen staining and culture for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Kathmandu University medical journal (KUMJ), 7(27), 226–230. https://doi.org/10.3126/kumj.v7i3.2728